Algorithm to suggest food inspections abandoned

Published:

updated March 2025

UK food inspectors have abandoned plans to use an algorithm in part of their food hygiene rating system after a £100,000 trial.

Fifteen local authorities took part in the six-week pilot in 2022. But in the end many local authorities found their own solutions to a post-Covid food inspection backlog, and the Food Standards Agency (FSA) said the automation raised too many ethical questions.

A “da” rating of 4 on an eatery window in Wales. Food hygiene here is “good”

The technology predicted two things: the hygiene rating of a food outlet that was waiting for inspection, and the probability that it would be broadly clean (a 3, 4 or 5 rating).

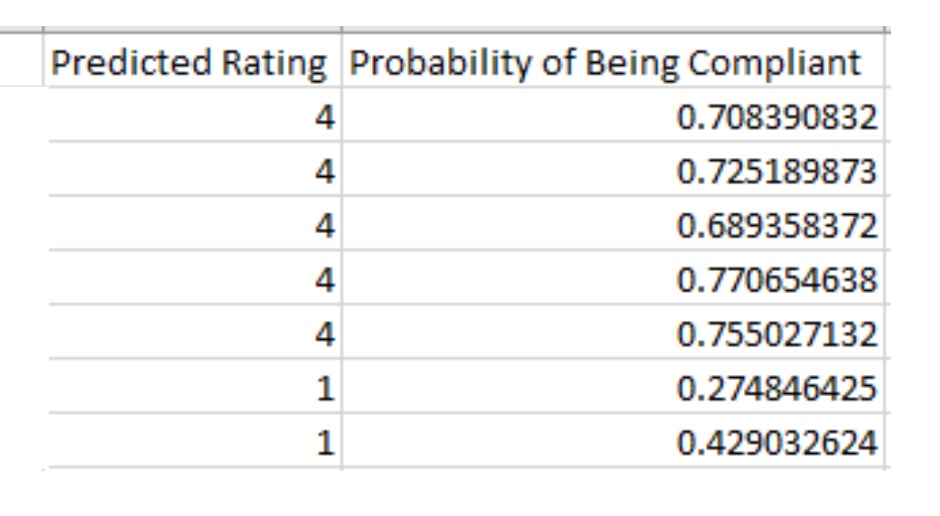

Screenshot of (part of) how the tool might respond when asked about a specific local authority, with the names of the area’s food outlets removed

Faced with a simple but pressing question after Covid, “Who should we inspect first?”, the FSA paid the technology company Cognizant to build this technology. The company’s model was to be used to identify which cases were most urgent, leaving local authority inspectors to establish the actual rating after a visit.

‘Urgent’ here meant those eateries that were predicted to fail an inspection.

The code used to train the computer model was released in response to a Freedom of Information request along with an outline of the kinds of data that, once supplied to the computer system, would generate the two predictions. I was given an outline of the variables, along with the code used to build the computer model. A second FOI request returned two pieces of documentation: a user manual and an Ethical AI framework.

A more detailed version of the machine’s response shows not just if an outlet is predicted to get a compliant rating (3-4-5) or non-compliant rating (0-1-2) but how likely it is to fall into a compliant category.

Part of a response, showing how likely it is that food outlets will get a higher, ‘compliant’ score of 3, 4 or 5

The FSA technology was ultimately shelved because the Agency decided there were “ethical concerns” that data on demographics and the type of food prepared in different outlets “could result in biases for certain types of businesses”. And by that stage, many councils had found their own solutions to the backlog.

How it works

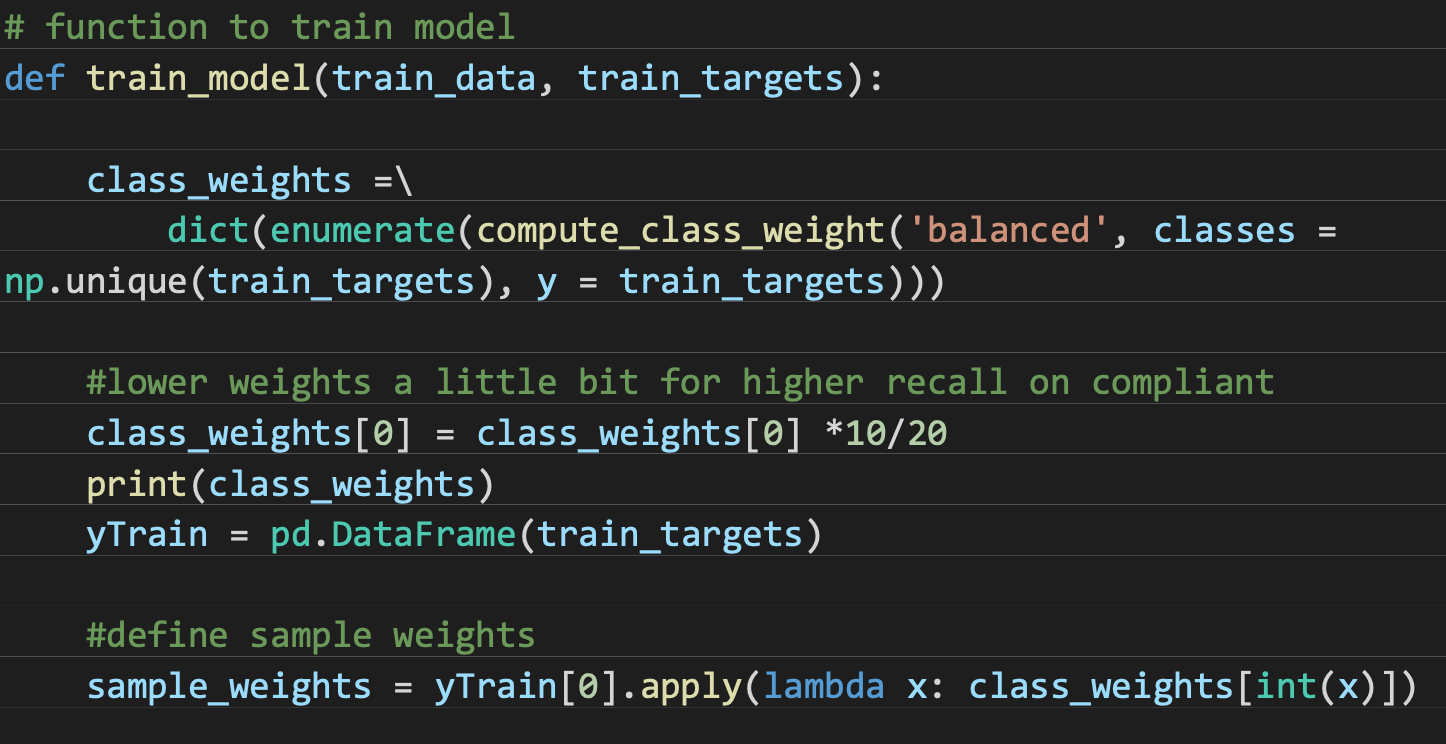

Some of the code that trained the model from existing data and generated predictions for new data

There are two main ingredients to all of this: 1. the data the machine examined to decide the probability that a food outlet wasn’t clean, and 2. the code that read the data, generated the inferences, and returned a recommendation.

Although we haven’t analysed the code in detail, we know already that it was based on three particular machine learning libraries: tensorflow, sklearn and lightgbm. (Libraries are third-party computer programs imported into some code to carry out particular tasks).

The data that the machine read, in order to reach its conclusions was of three kinds:

the Food Standards Agency’s own data: Is it a pub, or a hospital? Is it a chain restaurant? Which local authority is it in?

census information from the local authority area where the food outlet is located: population size, age structure and density; residents’ country of birth, passport and language; house prices and economic situation; employment data; life expectancy and disability rate.

retail information for app developers from an online database. As well as the kind of food business and the opening hours, this appears to have told the machine if the food outlet could be described as Chinese, Asian, Middle Eastern, Indian etc.

What we don’t have is the training data, i.e. the above information tied to previous Food Safety scores. Only by reading historical cases which link outlets to scores would the machine have been able to infer the likelihood of a new outlet being clean or dirty.

The Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard

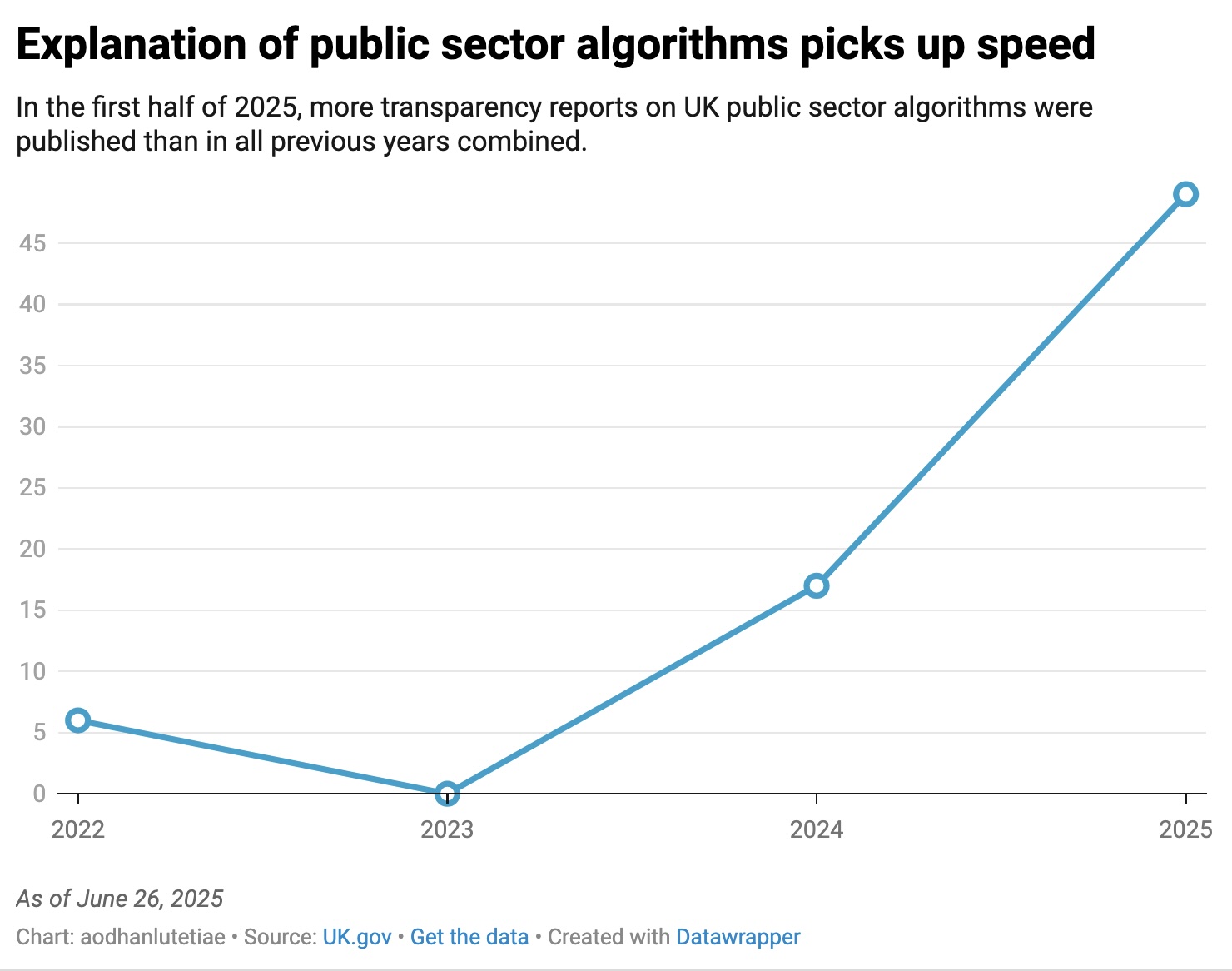

This technology was first described on a government platform to list algorithms that are used in the public sector: the Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard was launched as a trial in late 2021 (and was discussed at Open Data Camp 2023).

The details of just six algorithms were published the following year and publication resumed early in 2024 with the details of an algorithm developed for the Cabinet Office.

This year (2025) there has been a sharp increase in the number of algorithm details released: reports on 49 different algorithms used in the public sector have been published in the first six months of the year.

The Guardian reported that the Department of Work and Pensions uses a piece of AI technology to review correspondence and that this tool was absent from the transparency platform. There are presumably many others missing too, even if the government’s abandoning several proposed AI tools.